1. Select a discrete app icon.

notes

The Hidden Horrors of Reunification Camps

Family court judges around the U.S. are ordering children be taken by force from protective parents and sent away with abusers in a for-profit scheme

- Feb 14, 2024

It sounds like something out of dystopian fiction—children as young as 7 forced into “camps'' with an abusive parent, held captive until they admit that the abuse they were subjected to never happened. Run by unqualified individuals who see a way to profit off of the family court system, reunification camps hold children until they can convincingly feign affection for the parent that oftentimes controlled them, harmed them, sexually abused them or was abusive to their other parent in front of them.

And yet, in the majority of states in the U.S., this is a real and legal option in family court, and it’s happening every day to kids. Sometimes they’re taken from their beds in the middle of the night—a surprise attack meant to get them before a protective parent can hide them. Transported in vans to shady motels or empty office buildings, sometimes flown to other states, surrounded by strangers threatening them to comply, these already traumatized children may not be returned to a protective parent for weeks, if not years. Advocates say it’s akin to a legalized form of kidnapping and human trafficking. Courts say it’s a necessary step to rebuild a broken child/parent relationship. Victims say it’s a way to further silence the epidemic of domestic violence and sweep it under the rug.

Ally’s Story

Ally Toyos was 8 years old when her parents divorced. Like many kids in split families, she and her younger sister, 6, spent some time with their mom and some with their dad, who lived in separate houses in the same city in Kansas. Only, she and her sister dreaded the latter. Toyos says her dad was abusive—he took his anger for his ex-wife out on his two daughters through emotional, physical and sexual torture.

“My sister and I were scared of what he’d do if we told anyone. He overpowered us,” Toyos, now 22, says. He’d shove the girls into walls, pull their hair and much worse. And while he was their abuser, he was also their father, and the girls felt pressured to stay silent.

“We didn’t want anyone to get in trouble.”

DomesticShelters.org reached out to Toyos’ father but he declined to comment.

When Toyos was 12, her mom needed to relocate to Tennessee for a new job and wanted to take her daughters with her. In a family courtroom, the girls never imagined a judge would keep them from their mom, especially when they voiced that they felt safer and happier with her. Except, that’s exactly what happened. A family court judge ordered the girls to stay in Kansas with their father. The girls could see their mom two weekends a month when she was able to make the trip back.

Toyos and her sister knew they had to tell someone about their father’s abuse. They disclosed what was really going on to their therapist and their guardian ad litem, or GAL, a person assigned to represent a child’s interest in the court. To their shock, none of the adults seemed to be bothered. Instead, says Toyos, their GAL told them, “Sometimes we have to do things we don’t want to do.”

In all 50 states, therapists are mandated reporters and must report child abuse to law enforcement. Dr. Christine M. Cocchiola, DSW, LCSW, Coercive Control and Child Advocate, speculates why this happened. Cocchiola has never treated nor met Toyos, but she testified in numerous family court cases against family reunification therapy.

“Collusion. These therapists … diminish the abuse because they can make a case that the mother has forced the children to fabricate this. There’s money to be made.”

Indeed, what came next would be costly, but we’ll get to that in a second.

Toyos has her own theory on what happened.

“I think that they told our father what we said [about the abuse]. And he started to say he was being alienated.”

Alienated. By definition, to be isolated or estranged from a person or group that one should belong to. In cases of domestic abuse, child abuse and contested custody, this word has become weaponized, often by abusive fathers to accuse mothers of keeping children from them as a way to deflect from their abuse.

Soon, the girls would find themselves in a dizzying world of reunification, another word that may sound harmless at first, but is anything but in cases of abuse.

History of Parental Alienation Syndrome

In the 1980s, a psychiatrist named Richard Gardner coined a disorder called “parental alienation syndrome,” or PAS, which most domestic violence advocates and mental health professionals renounce today for its lack of scientific basis and its manipulative use in court. Abusers have been known to employ this term to convince a judge their partner is “brainwashing” a child into refusing to go to the abusive parent for visits. As a result, many survivors find themselves in the throes of a court battle to prove otherwise.

“Gardner made this up based on his own clinical observations with no science behind it,” says Mo Therese Hannah, Ph.D, founder of the Battered Mother’s Custody Conference and New York professor of psychology at Sienna College. “It’s a way to divert attention away from the attacker and onto the victim. It’s like a joke that was taken very seriously.”

PAS was found by a task force from the American Psychological Association to have a significant lack of data to support it as scientifically sound. It’s also not a diagnosis listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Diseases (DSM) or The International Classification of Diseases.

“Non-court-regulated psychologists haven’t even heard of it,” says Hannah. While the outcry over its lack of scientific basis has led to the term fading out somewhat in the last decade, Hannah says the theory itself is still being used. “If a mother tries to protect her child or distance her child [from the abuser] terms like ‘maternal gate-keeping’ or ‘alienation theory’ now come into play. The idea is, if a child is reluctant to be with one parent, the other parent is wrongly convincing the child of something that isn’t true.” Hannah calls it “so beyond what is real,” adding, “Any mother will tell you it’s hard to influence your child to do anything, especially when they’re older. These women are being accused of being magicians.”

The Industry Surrounding Alienation

Tina Swithin is the author of Divorcing a Narcissist and the founder of One Mom’s Battle, an online advocacy group for protective parents fighting against abusers in the family court system. The group was formed in 2011. It was around the time Swithin began her own ten-year journey through the California family court system where she successfully protected her two children from her abusive ex-husband while serving as her own attorney. In 2020, Swithin founded Family Court Awareness Month to bridge the disconnect between survivors and community members, many who aren’t aware these atrocities are being committed.

Family reunification camps are one of her main obstacles right now.

“If you would have asked me five years ago, I would have said they weren’t that common. But over the last several years, they’ve exploded,” she says.

Though they may be touted as a healing step to bring children and an estranged parent back together, Swithin says the reality is far from it. The motivation for these camps to exist is less altruistic and more financial, hence why you won’t often hear of lower-income victims being subjected to them.

Swithin says the least expensive camp she knows of costs $12,000 for four days of “therapy,” but the cost can easily soar over $100,000 once transportation is factored in. In one case, “transport agents”—the individuals assigned as pseudo-bodyguards to keep children from running away after being taken, went on vacation with the abusive parent and children after a reunification camp, racking up an astronomical bill in the process.

And who foots the bill?

“It depends who has the money,” says Swithin. “A typical case is a dad who is extremely wealthy. He’s willing to pay these fees because it hurts the mom the most. He’s essentially buying custody.”

In some cases, the cost is ordered to be split evenly, sometimes adding in the extra trauma of bankrupting the protective mother.

And then, of course, there’s the aftercare: Therapy required by the reunification camp organizers for both the children and the protective parent. Therapy that’s required if the protective parent wants to see their children again. These therapists, assigned by the reunification camp organizers, often “treat” the protective parent for alienation. And since it’s not an actual diagnosis, insurance is never accepted.

“The moms have to do whatever these people say,” says Swithin, remembering one case in which a mother had to write her children a letter saying she made up her allegations of abuse against their father and that nothing the children’s father ever did was bad.

“If they ever want to see their kids again, they have to do this,” says Swithin.

In many cases, Swithin says the so-called professionals who run these reunification camps aren’t therapists at all and have no mental health training. There are no regulations to open one of these reunification camps. Anyone who’s willing to call themselves an expert could open one tomorrow and begin treating children.

Yet, says Swithin, family court judges trust them as expert witnesses in the area of parental alienation. When these “experts” suggest a four-day reunification camp will aid in ending parental alienation, judges who don’t understand the dynamics of abuse are more likely to sign the order.

Cocchiola says family court judges are taking the word “alienation” and running with it, ignoring what could have led up to a child being afraid of one of their parents.

“The court doesn’t even say, let’s look at the foundation of this family system. What were the dynamics going on before the child decided they didn’t want to see this parent? It’s so harmful.”

Swithin agrees that a lack of education among family court judges is a huge part of the problem.

“Most states have zero requirements for judicial training on domestic violence, post-separation abuse, sexual abuse, trauma, etc. That’s difficult to grasp given that these individuals are making decisions that could literally affect the life of a child with no training," she says.

H. Lee Chitwood is a family court judge in Pulaski County, Virginia. He also chairs the Pulaski County Domestic Violence Committee. Though it varies by state, in Virginia at least, judges receive three weeks of mandatory training, which covers a wide variety of areas from domestic violence to child support, abuse to neglect. Additional training, on both the state and federal level, beyond those three weeks is available, he says.

"Some judges take every opportunity, and some do not. I am very passionate about domestic violence, but some judges fear losing the appearance of neutrality. They worry that collaborating with other agencies or having a domestic violence committee makes them appear too victim-oriented.”

And that choice can sometimes have dire consequences.

"Sadly, I know many mothers whose children have been murdered because of judicial rulings that put their children in danger despite their desperate pleas to the court," says Swithin.

If not murdered, then taken. Once children are sent away to these reunification camps, the four-day promise one issued is soon proven to be a myth, says Swithin.

“If they [the camp owners] go back to court after four days and say, ‘This is a severe case of alienation,’ the judges can extend that order for a year or more. The judges hand over full custody of the children to these non-experts.” Swithin says she knows a mom in Texas who hasn’t seen her kids in five years since they were ordered to go to a reunification camp.

Ally and Her Sister are Taken

Toyos and her sister were 16 and 14 respectively when Johnson County District Family Court in Overland Park, Kansas ordered the girls be sent to a reunification camp with their father called Family Bridges. Family Bridges was founded by a man named Randy Rand, a former psychologist whose license was revoked for unprofessional conduct. When contacted, Dr. Yvonne Parnell of Family Bridges told DomesticShelters.org, “We decline to give interviews to the press.”

“My mom had no idea what was happening until the night before,” says Toyos. “She was sent a court order to appear with us at the courthouse in the morning.”

The girls’ case manager was waiting for them with several transport agents.

“He said, ‘Do what we say and you’ll be fine.’ We were taken out the back door and my sister and I were put in separate cars.” Toyos was terrified.

“I kept thinking there was no way this could be real. I had no idea when I could see my sister again or what was going to happen to us.

According to the Family Bridges website, their workshops are offered throughout the United States, Canada and abroad, “with an increasing number of independent practitioners being trained to provide the workshop.” They go on to say, “The workshop usually takes place at a vacation resort facility rather than in an office.”

Toyos and her sister were first taken to a hotel where they would spend the night in separate rooms being watched by the transport agents, one man and one woman they’d never met before who didn’t allow them to even close the door to the bathroom. The next morning, the girls were put on a flight to Montana before winding up at a place called the C’mon Inn. That’s where workshop leaders were waiting for them, along with their estranged father and their stepmother.

“They said we weren’t allowed to talk about the abuse or anything that happened in the past,” remembers Toyos. “We’re not here to listen to your side of things,” said staff with Family Bridges.

They also told the girls they would not be able to contact their mother for 90 days.

From there, the “reprogramming” began.

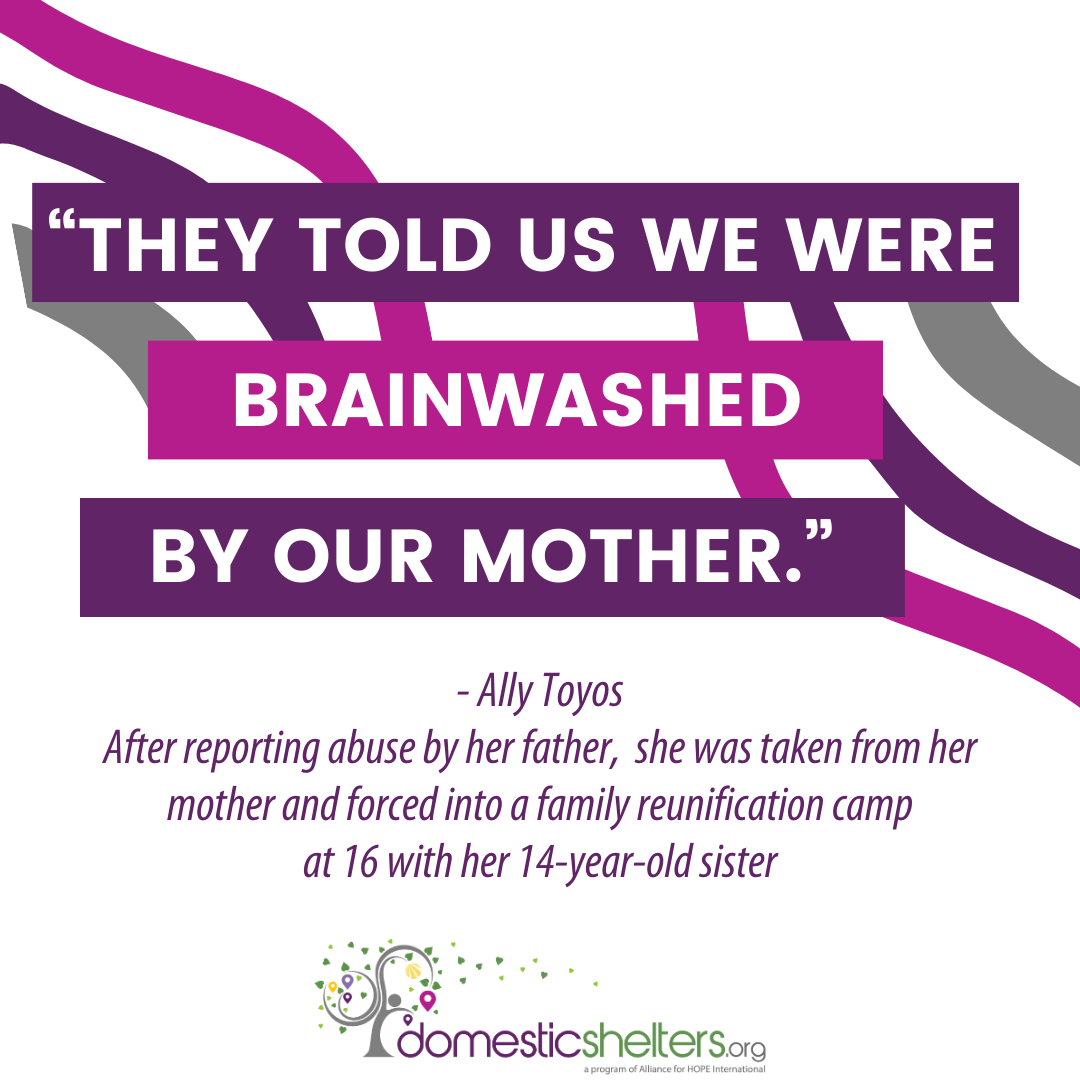

“Your mom has been abusing you, has alienated you from your father, and he’s a victim in this,” Toyos remembers them telling her. “None of the memories we have of our father abusing us are real and they told us we were brainwashed by our mother.”

The Family Bridges website says the goal with their workshops is to “teach children how to think critically; how to maintain balanced, realistic, and compassionate views of both parents; and how to resist outside pressures that can lead them to act against their judgment.”

It goes on to say, “Children who reject a parent after divorce, who refuse or resist contact with a parent, or treat a parent with contempt represent one of the greatest challenges facing courts, divorced families, and the professionals who serve them.”

For four days, Toyos says the girls were only allowed to speak if they wanted to say something in agreement with the reprogramming. They were forced to watch YouTube videos about the Milgram experiment from the 1960s where participants underwent shock therapy and learned to obey commands. They were forced to watch “The Wave,” a 1981 made-for-TV-movie about the Nazi regime.

“Everything was curated to make us believe that we couldn’t rely on our memories or real experiences,” says Toyos. “They tried to explain what parental alienation was and I said, ‘Isn’t this parental alienation?’”

If the sisters voiced any resistance, Toyos said they were threatened to be sent to a psychiatric facility, remote wilderness camp or foster care where they would never see each other or their mom again.

When the four days were up, the girls, their father and stepmother went on a “family vacation” to Las Vegas.

“I think my father had deluded himself into believing this worked. As long as my sister and I weren’t outwardly showing how much we hated him, he could pretend we were a happy, normal family.”

After that, they returned to Kansas to live with their father. It would be seven months before they could talk to their mom on the phone, says Toyos. They were given five minutes.

Another two months later, they were able to see her. After a tearful reunion, Toyos says her mother showed the girls news articles she had compiled of other children who had been subjected to reunification therapy.

“We’d felt like we were the only ones this had ever happened to,” Toyos says.

Today, both Toyos and her sister are in college. Both are pre-med. They’re close with their mother and don’t talk to their father. He never acknowledged anything the girls were subjected to at the camp, or otherwise.

Toyos has become an outspoken advocate against reunification camps and the first survivor of these camps to put her story out on social media. She founded the youth advocacy initiative, CJE Youth Speak.

“Through my work with CJE Youth Speak, I have been able to connect with other survivors, work with many protective parents to prevent their children from being forced into reunification camps and had the opportunity to educate judges, lawyers, social workers and the general public about the horrors of reunification camps and family court corruption,” she says.

Banned in Two States So Far

Colorado was the first state in the nation to ban reunification camps, thanks to Kayden’s Law passed in May of last year. And soon, California will follow suit, having passed Piqui’s Law last September. Both bills were named after children killed by abusive parents in unsupervised custody visits and both place much stricter qualifiers on family courts when making custody decisions. Still, these laws won’t necessarily prevent reunification camps from operating in these states, they’ll only prevent children from these states being forced into them.

Advocates and victims know there is still much work to be done. One barrier is simply getting the word out about them and convincing people that they’re real and not a legitimate form of therapy. Cocchiola calls these camps “the dark underbelly of family court.” Operating in secret has long been the key to their success. And it’s not hard to figure out how this happens—almost all victims of family reunification camps are subjected to gag orders. The protective parent isn’t allowed to talk about what happened to their children (Toyos’ mom is under a permanent gag order) or they may be punished with an even longer wait to get their children back, says Swithin. And the children who are forced into the camps are silenced as well, at least until they age out at 18.

“It’s reached crisis level at this point,” says Swithin. “But we’re going to see change as these kids age out of the system…we’re going to see them speaking out.”

Attention to this crisis was bolstered further when a 20-minute documentary was released in November on YouTube showing graphic scenes of children being taken by so-called transport agents. Currently, there is also a pending civil suit in which at least 15 victims are taking on one particular reunification camp.

It means survivors like Toyos finally get to have a voice.

“Getting this out there so people understand it’s happening is really healing. It’s no longer something that can happen in secret.”

Donate and change a life

Your support gives hope and help to victims of domestic violence every day.